Preparation is the key to successful rapid antigen testing in the workplace.

Staff numbers, testing sites, reporting systems and delivery were the types of factors employers needed to consider before implementing a program, those attending our webinar, The ins & outs of Rapid Testing: how to make workplaces safer from COVID-19, heard yesterday.

Panelist Simone Robinson, Head of Operations at Hough Pharma — which supplies government-approved rapid tests — said more than 1 billion rapid antigen tests had been administered worldwide.

“If you really think about this process and set it up from the start, it can run very smoothly,” Ms Robinson said.

“It doesn’t have to be cumbersome or difficult. It needs a bit of preparation.

“The organisation needs to think about some key issues and design a program based on the answers that they have to their individual circumstances.”

Questions to ask include:

“They’re questions that you really need to think about as an organisation and that will help you form your testing program,” Ms Robinson said.

“It’s about workplace safety, particularly in high-risk industries like those in aged care or where employees are in contact with a significant number of members of the public.

“The other reason people might want to use rapid antigen testing in the workplace is that they may have high-risk locational operations.

“In areas where staff are concerned about coming to work because of COVID, a rapid antigen testing program may create a more positive staff culture, so people feel like they’re coming to work in a safe environment because there’s a regular testing program in place.”

Ms Robinson said there were two testing models: in-house programs under the supervision of a medical practitioner and outsourced programs.

In-house programs are suitable for larger organisations with multiple working sites, cost-effective and tailored to the needs of each employer.

Outsourced programs were more suitable for smaller organisations but came with a higher cost per test and took more of a standardised approach, Ms Robinson said.

“If you’re testing 100 staff versus 5000 staff, the way you design a program is going to be vastly different,” Ms Robinson said.

“If you’re considering putting rapid antigen testing in your workplace, have a lot of conversations with people and ask them questions.”

Fellow panelist Adjunct Prof John Skerritt, Head of the Therapeutic Goods Administration, said rapid testing was not as sensitive as PCR testing, which remained the definitive diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection.

For rapid antigen testing to be used successfully in the workplace, regular screening was essential, Prof Skerritt said.

“One of the reasons for there being certain regulatory controls on these tests – and how they are used — is that they are not definitive,” he said.

“They do not have the sensitivity of the PCR test. You can be negative in a rapid test and unfortunately still be positive and you can be positive in a rapid test and fortunately still not have COVID.

“There’s this trade-off between speed, convenience, doing something that’s like a home pregnancy test and something that is able to be the definitive diagnostic test.

“The two are not equivalent. That’s why, at the end of the day, a PCR test is absolutely critical for anyone who either feels they have the symptoms of COVID or comes up positive in a rapid antigen test.”

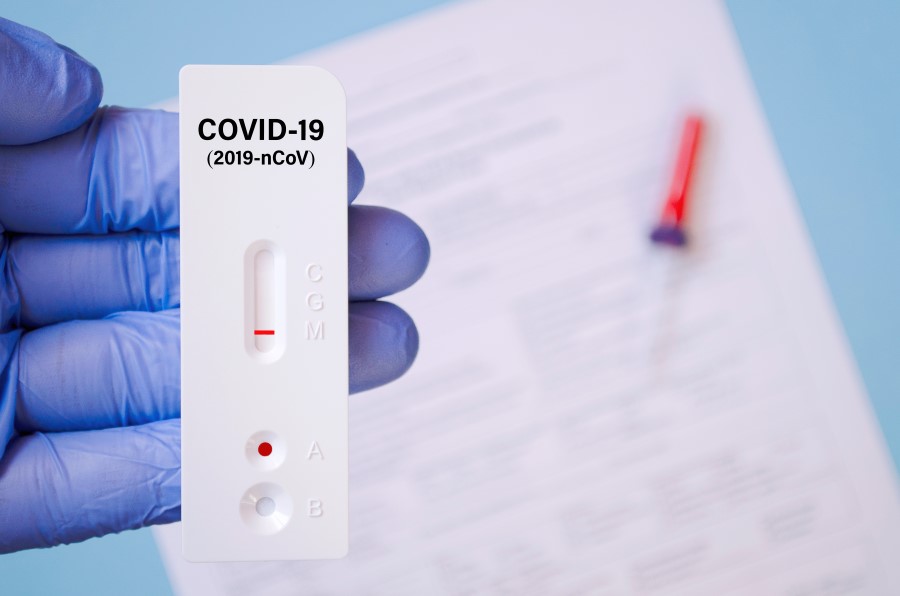

Prof Skerritt said there were currently 28 rapid antigen tests available.

They work by detecting the protein coat of the COVID virus.

“Rapid tests work very well just after you get infected and in your first week or two of infection,” Prof Skerritt said.

“If someone has symptoms, send them off for a PCR test. Don’t get them to come to work and have a rapid test.

“But if someone doesn’t know, and you want to check them, to give them a degree of confidence because they’re working with others, the message is to be transparent about accuracy.”

Prof Skerritt said it was important to remember that a company could test its own staff but was not authorised to offer a testing service for customers and the wider public.

“There is no requirement for a doctor or another health practitioner to be physically present when the tests are done,” he added.

“There is a requirement for someone to oversight the tests – it could be the proprietor of a small or medium-sized business. What they do need is access to a nurse or pharmacist on tap. It can be by video or phone for advice.

“We also want them to have done some initial training, which could be done through a 10-minute Zoom call.

“If you test more often – and the fact you’re getting immediate results rather than waiting several days while people may be infectious in the community, if they don’t isolate – there are those advantages to rapid test.

“You lose a bit of the downside if you regularly test.”

Prof Skerritt said controls around rapid testing could be reduced when vaccination rates increased.

“We do expect we will move to a world where rapid antigen testing will be freely available in a less supervised, less controlled environment,” he said.

“The triggers for that will relate to vaccination rates. All the implications of a false negative test are reduced when we’re sitting at 70% or 80% full vaccination.

“At the moment, with lower vaccination rates, those downside risks are quite significant.”

Ai Group National Head of Workplace Relations Stephen Smith said challenges often reported by employers considering rapid antigen testing included cost, organising supervision by a health professional and prohibition on employees using the tests at home, unlike in the UK.

However, some employers have already successfully introduced rapid antigen testing and there have been trials within the NSW construction industry and in some large manufacturing plants.

Wendy Larter is Communications Manager at the Australian Industry Group. She has more than 20 years’ experience as a reporter, features writer, contributor and sub-editor for newspapers and magazines including The Courier-Mail in Brisbane and Metro, the News of the World, The Times and Elle in the UK.